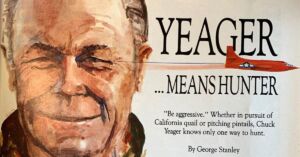

In Honor of General Chuck Yeager

Life long hunter, outdoorsman, test pilot , war hero (February 13, 1923 to December 7, 2020)

This story about Chuck Yeager the conservationist was originally published in Ducks Unlimited magazine in 1987 as part of a special issue commemorating the organization’s 50th anniversary.

This story about Chuck Yeager the conservationist was originally published in Ducks Unlimited magazine in 1987 as part of a special issue commemorating the organization’s 50th anniversary.

On the small side of average in physical stature, Yeager’s status among men is intimidating. Many have compared his charisma with that of John Wayne, but Yeager fired bullets where Wayne shot blanks. Still a teenager in World War II, Yeager shot down five German planes on a single mission, four on another. Shot down himself over Nazi-occupied France, he made his way toward neutral Spain with aid from the French underground, then ended up carrying a badly wounded American navigator over the Pyrenees Mountains to safety. Once back in England, Yeager protested a mandatory return stateside so vehemently that his request to go back to battle was personally heard and approved by Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower. Later in 1944, Yeager attacked and destroyed a newly developed German jet fighter that could fly much faster than his propeller-driven P-51 Mustang. He still feels today that “a superior pilot will beat superior technology.” But match a pilot of Yeager’s skill with top-flight technology and you’ve set the state for some legendary stuff.

Yeager’s name became legend among pilots on October 14, 1947. Shortly after eight that morning, he cooly pushed the X-1 rocket plane past Mach 1, the speed of sound, vanquishing a “barrier” that many pilots and engineers thought would obliterate any flyer who ventured too near. A hunter since childhood, Yeager figured that if natural forces allowed a bullet to travel faster than sound, they would allow a bullet -shaped airplane to do it as well. Once Yeager brushed aside the sound barrier, manned space travel became a possibility rather than a dream.

Y eager remained the world’s fastest human for most of the next decade, competing with other top research test pilots to set higher and higher speed records. Upon raising the record to Mach 2.4 in 1953, in a flight that nearly killed him, Yeager was described by Newsweek as “the man of the supersonic age. He is today’s pioneer and tomorrow’s legend.” For the most part, however, the legend of Chuck Yeager stayed confined within the fighter pilot fraternity until Tom Wolfe’s 1979 bestseller, The Right Stuff. Though Yeager’s story was told in one chapter, his presence dominated the book. He was, as Wolfe described, the top of the pyramid, the pilot other fighter jocks strove to emulate “the most righteous of all the possessors of the right stuff.” In the movie version of Wolfe’s book, Sam Shepard portrayed Yeager. Barbara Hershey played his wife, Glennis. The movie paved the way for a 1985 autobiography that became a number-one bestseller. A film based on Yeager is in the works. Even so, when Chuck crams into the cab of an old pickup with you and another 200-plus pounder, you realize that he’s not likely to be featured soon on “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.” In fact, as you head to a get-together with the owners of the Red Ranch Duck Club where you’ll hunt in the morning, Yeager talks as if he’s still sweating to support a wife and four kids on lieutenant’s wages.

eager remained the world’s fastest human for most of the next decade, competing with other top research test pilots to set higher and higher speed records. Upon raising the record to Mach 2.4 in 1953, in a flight that nearly killed him, Yeager was described by Newsweek as “the man of the supersonic age. He is today’s pioneer and tomorrow’s legend.” For the most part, however, the legend of Chuck Yeager stayed confined within the fighter pilot fraternity until Tom Wolfe’s 1979 bestseller, The Right Stuff. Though Yeager’s story was told in one chapter, his presence dominated the book. He was, as Wolfe described, the top of the pyramid, the pilot other fighter jocks strove to emulate “the most righteous of all the possessors of the right stuff.” In the movie version of Wolfe’s book, Sam Shepard portrayed Yeager. Barbara Hershey played his wife, Glennis. The movie paved the way for a 1985 autobiography that became a number-one bestseller. A film based on Yeager is in the works. Even so, when Chuck crams into the cab of an old pickup with you and another 200-plus pounder, you realize that he’s not likely to be featured soon on “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.” In fact, as you head to a get-together with the owners of the Red Ranch Duck Club where you’ll hunt in the morning, Yeager talks as if he’s still sweating to support a wife and four kids on lieutenant’s wages.

“I religiously change my oil every 3,000 miles. Oil’s cheap,” he says, in an accent as thick as the woods outside Hamlin, West Virginia the remote Appalachian mining town where he grew up the son of a gas driller. He talks as if there were no books or movies about his life, no television commercials, no speaking engagements at $20,000 a pop; as if he hadn’t made it all the way to general, from private, in his 35-year Air Force career. The changes, it appears, haven’t changed him.

You pull up to the house trailer that serves as Bob Petersen’s hunting headquarters. Yeager hops out , introduces himself to Petersen, then grabs a handle on a crateload of Dungeness crabs and helps carry it inside. The trailer is full of duck hunters with their wives and adult children. Chuck shakes hands, smiles at cameras, and tells jokes. He finds it highly amusing when Herb Jensen, who flew bombers over Germany in World War II, tosses a crab shell towards a trash bag and lands it short smack in a dish of seafood sauce. “No wonder you guys were dropping bombs on friendlies over there,” Yeager says. He calls everyone by their first names and expects them to do the same. He’s quite good at remembering names of persons he’s just met. “Only common ones,” he’ll say later. “I can pick up the common ones. If it’s an uncommon name, I won’t even try. I have a limited mental capacity and I’ve gotten to the point where if it’s not something that affects my longevity, I don’t much give a damn.” Moderation in drinking and a good night’s rest, he’s decided, are longevity enhancing. Two beers and 10 p.m. are enough. Back at the motel, you say goodnight and head to your rooms. “I’ll be out here at 5:15,” Yeager says. “Standing at attention.”

The plates on Yeager’s Chevy Blazer read “Bell X-1.” An open pack of chewing gum lies by the stick Beemans, the same brand he ritually borrowed from flight engineer Jack Ridley in the movie “The Right Stuff.” “They still make it in Canada,” Chuck says, offering a stick. Out at the marshes, in the dark of predawn, you split up in teams, then head for the blinds. Yeager wades toward a pit with Jensen, a Sacramento attorney. “How do you tell a lawyer from a rattlesnake?” Chuck asks. “How?” Jensen grumbles. “Lay them end-to-end on a highway. When you come back, the rattlesnake will have skid marks in front of it.

Despite the low clouds and haze, it’s light enough at legal time for Jensen and Yeager to begin filling their limits. Yeager’s eyesight is still 20/10, same as in the mid-forties, when he could spot German war planes at distances of 50 miles and more. He has no problem sighting in the ducks but appreciates help in identifying them on the wing. “I’ve always been more of a quail hunter than a duck hunter,” he says. Flocks of pintails skim through the sky with the grace of rowing crews gliding across calm waters. Now and again, in the distance, a large flock funnels slowly down to a rice field like a swarm of honeybees returning to a hive. But it is mostly small clusters of mallards and wigeon that answer Jensen’s call and circle within range. Yeager hasn’t fired his Model 12 in 30 years, since he gave it to his oldest son, Donald. He borrowed back the weathered Winchester specifically for this duck hunting trip after he and his son successfully bagged elk with muzzleloaders near Donald’s Colorado home.

Chasing fast-flying valley quail has kept Chuck’s bird’s eye sharp. He and Jensen waste just three shells between them in collecting two five-duck limits before 9 a.m. “In the military, we were never really privileged to the luxury that sportsmen have,” Chuck says after a plucking party outside the club trailer. “You’d just grab a gun and walk up the side of a mountain. That was hunting.” Over the years, Yeager has managed to hunt and fish on many mountains: from the Appalachians of his boyhood to the German Alps to the California Sierras to the Himalayas of Pakistan to the Alaskan Rockies. Yet he has never before hunted ducks in the foggy bottomlands of California’s Central Valley waterfowl mecca of the Pacific Flyway though he lives only 40 minutes’ drive up the road. Most of the valley’s prime waterfowling areas are leased or owned by private clubs. “Basically, I hunt on public lands,” Chuck says. “Hell, it’s good hunting. But the reason I’m successful is I work damn hard at it. I don’t hunt along the roads; I go up the side of the mountain that’s where the game is.” Chuck gets together with family and friends in several states every year to pursue elk, deer, turkey, geese and quail. He still backpacks into the High Sierras after golden trout each summer, hiking an average of 13 to 15 miles per day.

But he says his richest outdoor experiences came during the mid -fifties, while serving as a squadron commander in West Germany. “The best hunting in the world, by far, is in Germany,” he says. “They’ve been hunting there for 2,000 years and their hunting is as good now as it ever was.” Tremendously impressed by the German system of game management, Yeager immersed himself in “beautiful hunting traditions that have been passed down over hundreds over years.” In time, he became one of few foreigners allowed to lead a German driven shoot as a “Jägermeister.” “In its original spelling, Yeager is spelled Jäger, and means hunter,” Chuck says. “The Jägers have great respect for their animals.”

To be continued: