Last month, we discussed Arthur Amory, one of the six founders of the Lighthouse Club on Currituck Sound in 1874. You will recall the decoy stamped/branded with his name, and that he was from a Boston Brahmin family, an 1862 Harvard graduate, and member of Harvard’s Porcellian Club. While we didn’t know the carver of the Amory decoy, this month’s discussion provides some evidence of what could be its origin. As part of the larger group of decoys acquired by Mark Cromwell, three are stamped/branded “G G Hammond.” Upon initial reflection, one is left to wonder who that might be. After all, we have only initials and a very common last name. However, in our case we are putting together a puzzle—we know where a piece goes by how it fits onto adjoining pieces already in place. In this case, what we know about Arthur Amory tells us with certainty who G. G. Hammond is—i.e., Gardiner Greene Hammond, Sr. (According to entries in the Lighthouse Club logbook, Gardiner Greene Hammond, Jr., 1856—1925, was too young for our timeframe.) Arthur Amory’s mother was Mary Copley (Greene) Amory, a daughter of Gardiner Greene (1753—1832) who was the wealthiest man in Massachusetts in the latter 1700s—early 1800s. Arthur Amory was Gardiner Greene’s grandson through his mother. You will recall from an earlier edition of our chronicles that Gardiner Greene owned thousands of acres of sugar, cotton, and coffee plantations in Guyana on the coast of South America between Venezuela and Brazil. Greene spent much time on those plantations himself, from which he exported the sugar, rum (distilled from molasses, a sugar derivative), cotton, and coffee he produced to Boston and then throughout the colonies.

This was done during the time when sugar was king—when the value of sugar produced in the Caribbean Basin was worth many times more than the sum total of everything produced in the thirteen colonies. Gardiner Greene was at the forefront of the sugar business, and he built an immense fortune through that and other of his enterprises. His lineal descendants most certainly benefitted from his good fortune.

Our Gardiner Greene Hammond’s mother was Susannah Copley Greene, also a daughter of Gardiner Greene, making Hammond, too, a grandson of Gardiner Greene through his mother. Amory’s and Hammond’s mothers were sisters, making Amory and Hammond 1st cousins. While Amory was old-money wealthy from his father’s side of the family, he still followed and worked in the Amory family’s merchant footsteps, ultimately owning, among other things, profitable cotton mills in New Hampshire (Nashua Mills) and Alabama (Indian Head Mills). (In the latter half of the 1800s, many righteous northerners were highly critical of the exploitation of child labor in southern mills like Indian Head, which, ironically, was owned by a blue-blood northerner!) In other words, Amory still at least appeared to be striving to further enrich himself. On the other hand, however, Gardiner Greene Hammond’s obituary noted that he “…never was engaged in active business life.” Apparently, he enjoyed his gilded-age existence while being gainfully unemployed, if you will. Although he and his brother, Samuel Hubbard Hammond, were orphaned at an early age, they both were educated at Harvard, after which they devoted several years to European travel. (Remember the Hubbard name—we will see it again in a later edition. Blue Bloods married other Blue Bloods, almost exclusively!) It’s impossible to imagine their travel was done on the lam or even a shoestring budget. After returning to Boston, in 1856 Gardiner married Elisabeth Crowninshield Mifflin. (Remember, too, the Crowninshield name—we will revisit it in a subsequent edition of these chronicles and experience a rich piece of our nation’s history, from the 1700s to Watergate in the 1970s. For now, however, I will share that Elisabeth was a granddaughter of Benjamin Crowninshield (the first of that name), U.S. Sec’y of the Navy under Presidents and Founding Fathers Madison and Monroe. His grandson Benjamin Crowninshield (the second of that name) was a Lighthouse Club member we will hear about later—there’s considerably more to learn about the Crowninshield’s.) Because Hammond never worked professionally, our knowledge of his life is limited. However, we do know from the evidence we have that he used the decoys pictured when hunting at The Lighthouse Club. We will also learn later that he was just one of a number of Arthur Amory’s relatives and fellow Harvard graduates who were members and hunted at the club.

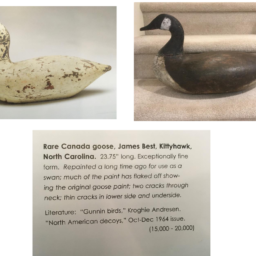

Gardiner Greene Hammond’s decoys also give us a clue as to where a number of the club’s decoys might have been carved. (Keep in mind that these decoys are 130+/- years old. A large portion of the Lighthouse Club logbook entries preceded 1890.) We have a group of decoys very similar to Dodge factory birds (Dodge began production in the 1880s). We also have a number that Mark suggests may have been carved in Connecticut, to include the Hammond and Amory birds, as well as others we will explore later. It turns out that our Gardiner Greene Hammond had a widely celebrated summer home in Waterford, CT. “Walnut Grove” is noted as “…the former estate of the Hammond family, descendants of a wealthy Boston merchant <i.e., Gardiner Greene>.” It is currently a National Historic Site and a well-preserved example of a ‘gentleman’s farm,’ as the photo below reveals. Gardiner Greene Hammond, Sr. acquired the property in 1862. With his Waterford estate’s proximity to Long Island Sound, it is well within reason that Hammond acquired these decoys for himself and fellow Lighthouse Club members from a local carver he knew of in Connecticut or perhaps even Long Island, which has also been suggested as an origin of the Amory decoy. Perhaps one day, that mystery as well will be solved.